Creation of problem set on Sudanese Colloquial Arabic

For one of my core classes in the PhD curriculum at the University of Chicago, I created a problem set for undergraduates based on data from Sudanese Colloquial Arabic.

Overview

In my Phonological Analysis 2 course, taught by Professor John Goldsmith, we each created a problem set to give to a hypothetical group of undergraduate students (I’m sure John had this in mind, but I’m not sure if he knows that I’ve used parts of this problem set for every one of the classes I’ve been a teaching assistant for or have taught). My project was on Sudanese Colloquial Arabic. We were tasked with curating a data set with several questions to lead the students through an analysis which would uncover a concept we found important. At the time I was just getting introduced to more formal ways of expressing theories, so you will see a heavy emphasis on basic set-theory; additionally, I had been (and remain to be) interested in ways to pare down on theory, as I often think that the heavy theoretical frameworks with which we work are often not relevant for reality (I was also pretty fresh off of reading the work of Trubetzkoy and structuralists at this point, which I found to be very inspiring), and this lead to me constructing a problem set which focused on positing a minimal set of features to explain the alternations in the data. I’ll briefly go over the problem set.

Data

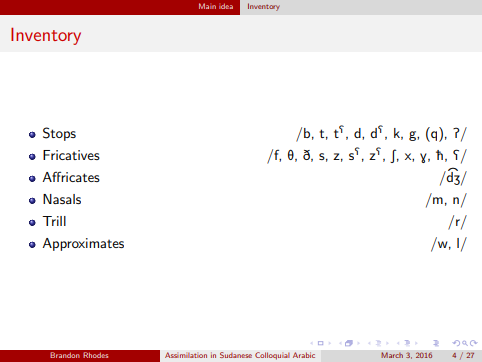

The data comes from the Sudanese variety of Arabic. More generally in Arabic, consonant-consonant (CC) combinations, especially at morpheme boundaries, are typically ‘repaired’ (read as: changed) in some fashion. So, as a case study for this problem set, I used modified nouns, which consist of noun-adjective sequence. Below, you will see the obstruent (read as: consonant) inventory for Sudanese Colloquial Arabic (SCA), as well as a set of data points (though this is not all the data).

Observations

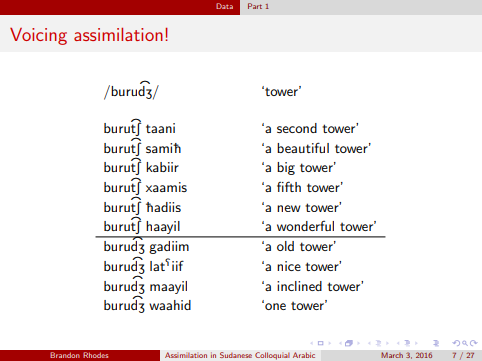

The main observation is that at the word boundary — so, the end of the first word and the beginning of the second word — we see an alternation in the final consonant of the first word, depending on what the second word is. This alternation is governed basically by a few things: (i) voicing, (ii) place and (iii) emphasis. There are a couple of patterns you can see in the data:

-

Voicing assimilation, but not with [l, r, m, n, w] — so, the last consonant of the first word becomes exactly the same as the first consonant of the second word, except with the mentioned consonants.

-

Total assimilation — so, the last consonant of the first word becomes similar in a particular way to the first consonant of the second word, but not completely the same.

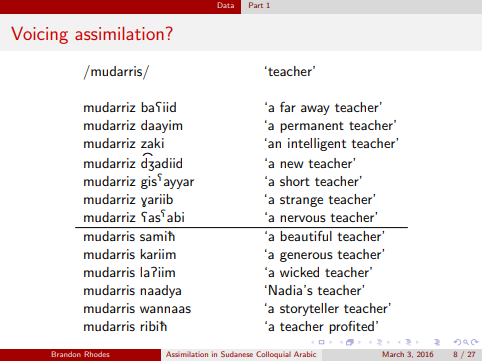

You can see the problem set (with suggested analysis) or presentation for a more thorough explanation and more details. Then, as is common with all linguistic data sets, I present a batch of data later, which introduces another pattern which most likely will change the current analysis. This data is shown below, and the observation is that there is a necessary contrast we need to make between consonants, and I call this ‘emphasis’. Emphatic consonants pattern with each other but not non-emphatic consonants; so, emphasis is a dimension on which consonants are contrastive in this variety of Arabic.

Quick notes on the analysis

As I just alluded to, the goal for the analysis was to use the data to motivate contrasts in the phonology for Sudanese Colloquial Arabic. The first observations will lead to voicing, place and manner contrasts, which are pretty normal, but second batch of data will lead to this contrast in ‘emphasis’, which is a bit more abstract, one of the defining characteristics of phonology. We typically formalize this with a bit of notation, but I will leave that for people to read on their own, if interested.

More information

Here is the problem set itself, the suggested analysis and the presentation for this project. Thank you, John, so very much for having us do this; also, thank you even more for my ‘welcome-to-UChicago’ moment. There was a time in our meeting for this project where I tried to slide some inadequate work (read as: bullshit) by you, and you let it be known that it was inadequate (read as: shit) in a tough-love kind of way. I respond well to that type of feedback however painful it may be at the time. This was the moment that I knew I wanted to work with you in the future.