Language in preschool instruction

A reanalysis of a PNAS paper on the effect of engaging language on preschoolers' persistence and interest in learning about science.

Overview

This is a project I did for the class Data Analysis Project (STAT 34900) taught by Professor Peter McCullagh. I reanalyzed some of the data from the paper Asking young children to “do science” instead of “be scientists” increases science engagement in a randomized field experiment in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). The data I reanalyzed pertained to students’ persistence in learning about science. The authors of the paper report that usage of action-oriented language had no effect on students’ persistence and usage of identity-presupposing language decreased it: I argue in my project that there is not much evidence for an effect in either direction. I suggest that if there is any effect, it is pretty small.

Background and scientific interest

Researchers at NYU (Marjorie Rhodes and Amanda Cardarelli) and Princeton (Sarah-Jane Leslie) were interested in how certain language is related to student interest and persistence when learning science. The first type of language, which the authors of the paper suggest is the more default language, is `identity-presupposing’ language. This type of language suggests a student must first assume (presuppose) the identity of a scientist to learn about science. Here are a couple of examples in the context of a teacher exciting their students about a science lesson.

Let’s be scientists today! Let’s put our science hats on today!

In the first example, the student must accept the idea that they are a scientist, and in the second they must accept the fact they need a special hat to study science. The second type of language is action-based language. This type of language occurs when there is no such scientist/alternative identity the student must assume and instead contains language which solicits participation. Here are a couple of examples in the same context as before.

Let’s do science today! Okay, the steps of doing science are prediction, observation and checking.

The idea is that action-based language removes the potentially detrimental assumption a child must make to study science which occurs in identity-presupposing language. The authors note that identity-presupposing language can inadvertently decrease students’ engagement in learning science as well as create sex and racial disparities in these outcomes, as the archetype of the scientist often is not in alignment with the physical appearance of many students.

Experiment

The authors carried out a randomized field experiment on preschools in New York City. Looking at preschoolers is presumably of most interest, as they are young enough to be less likely to consciously register some of these linguistic cues (not that I am suggesting older students would always notice these cues). Depending on the school, the researchers gave teachers in the school one of two videos to train them on the science lesson they would give to their students. The lesson was on friction, as can be seen by the picture below. The experimental video contained an implicit emphasis on action-based language while the control video contained no such emphasis. The idea was that this implicit emphasis should be enough to change a teacher’s linguistic behavior. There is strong evidence to support the efficacy of this part of the experiment.

As you can see from the photo, teachers were tasked with teaching students about what friction does to a car’s motion down a ramp. They showed the students that ramps with varying materials would lead to different stopping points for the car on the bottom. I wish I could have been there to see the kids learn this! :)

Measurements

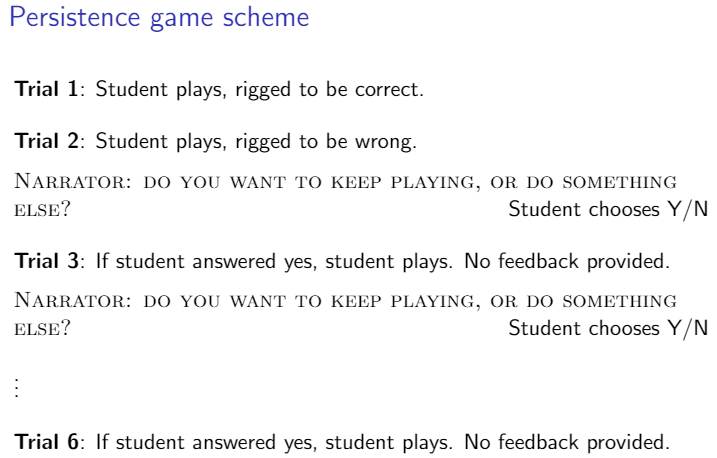

The researchers made many measurements, but I only analyzed a couple of the main ones. The first pertained to student persistence in learning science, which I will explain in more detail in just a minute; the second pertained to the efficacy of the experiment to get an idea of how much teachers’ language actually changed if they received a training video from the experimental condition. These teacher measurements amounted to counting and classifying various uses of the word science. Details can be found in the original paper or my final report or my final presentation. The persistence measurements are a bit more involved / indirect. You can see the measurement scheme below, and I will explain after.

The researchers came to each of the schools in the experiment within a few days of the student receiving the lesson on friction and had them play a video game on a tablet which resembled the lesson they received on friction; so, they had to guess how far a car would go down a ramp, given the material of the ramp. Each child was made to play two trials: on the first, no matter what they answered, the game would tell them they answered correctly; on the second, no matter what they answered the game would tell them they answered in correctly. It is after this negative feedback that students could play the game for up to six additional trials, choosing when to stop. The number of additional trials of the video game a student played was considered their `persistence’ since these trials occurred after the game was rigged to make them answer incorrectly.

My reanalysis

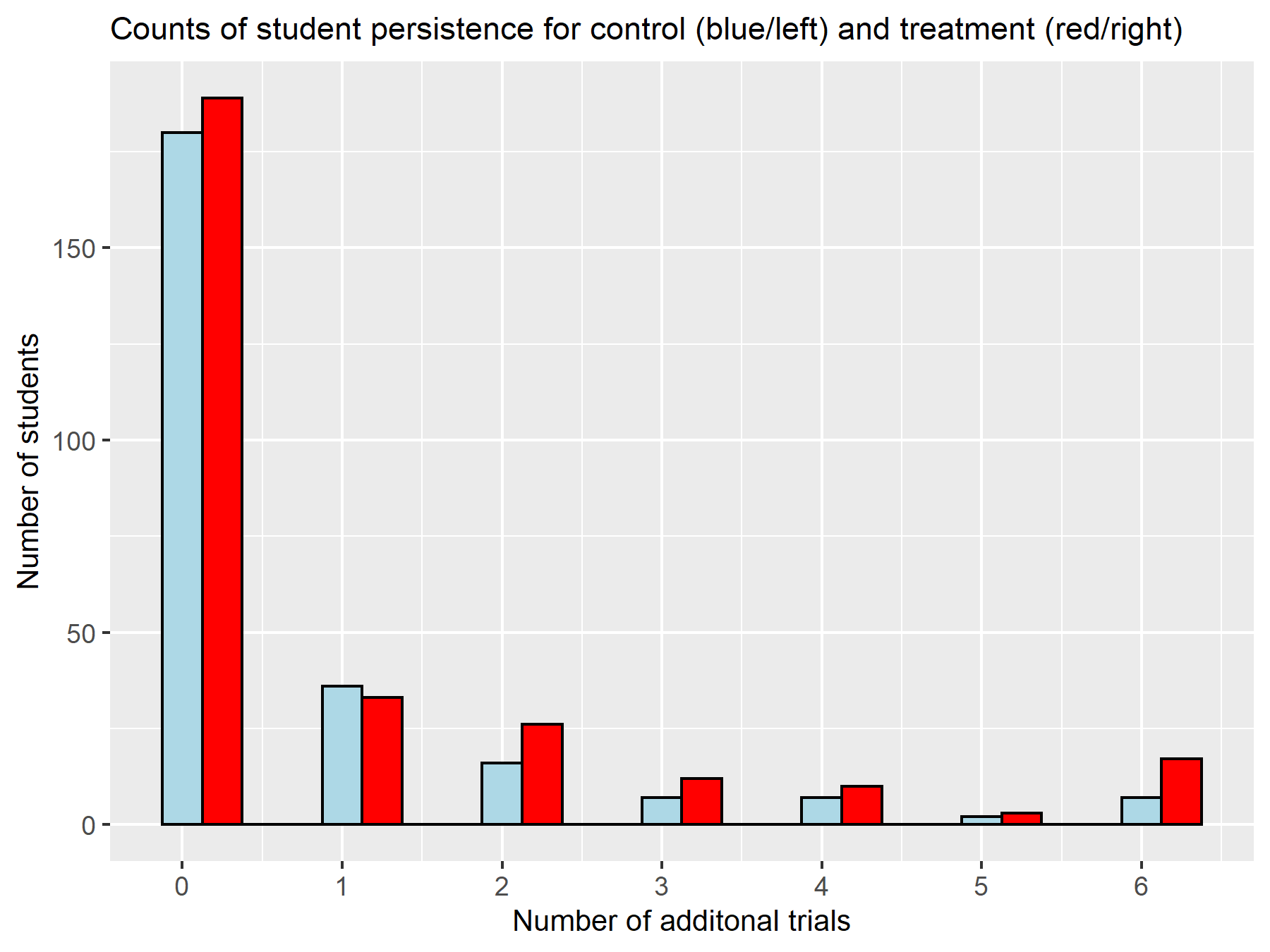

I used a different model to analyze the persistence data. The authors did a great job in capturing a lot of the structure in the units — in other words, they aptly accounted for correlations among students in the same class, teachers at the same school and schools within the same district — but I think they could have used a more appropriate model to capture structure in the experiment. They did not account for what is called censoring. An observation is said to be censored when you do not know the final outcome of an experiment/treatment. This phenomena is ubiquitous in medical, pharmaceutical and engineering studies. For example, suppose we want to measure the lifetime of some type of electrical units over the course of a month. Some units may die at various points within the month, but others may survive past that month after which we stopped our measurements. The point at which these units fail (die) is not known to use as the analyst. This is censoring. In this situation, students who played the game the maximum of six times are considered to be censored. We can see that there definitely happens in the experiment by looking at the image below.

The decreasing trend of students who played zero to five trials and then the increase/accumulation of the number of students who played six additional trials suggest we need to account for censoring in the model. I did this in my reanalysis. The histogram does suggest there may be some effect, especially at the accumulation point of trial 6, but this may be due to random variation. I’ll comment on this briefly below. The other points where I differed in my analysis were when it came to the measurements of the teachers’ language. I think the authors did not include some important linguistic structure in their analysis, such as normalizing by the length of a teacher’s or by noting the exclusivity of some of their categories. This I won’t go into much detail, but you can see in the final report.

Upshot

For this experiment at least, I am not convinced that the type of language a teacher used, as classified by the authors of the paper, had an effect on students’ persistence. The varying number of students between the control and experimental groups for six additional trials suggests that the authors may want to consider a more targeted experiment, but the authors note the difficulties in this, which I totally understand. We also need to keep in mind that even if the estimated effect for the treatment is accurate, which means it changes the odds by 1.3, this does not do that much. For example, if a child has a 50\% chance of quitting after the third trial, then that same child would be estimated to have a 43\% chance of quitting if they received instruction with an emphasis on action-based language. Undoubtedly, this is better, but not by much. As you can see from the histogram above, most students didn’t want to play the game anyways; maybe they were discouraged by the negative feedback or were just bored. One good thing about the reanalysis is that it gave me some hope that students from underrepresented groups may not be affected by inadvertent usage of particular language.

For more information

Please feel free to contact me with any questions about my reanalysis! This was a such a fun project, and I thank Professor Peter McCullagh for his time and feedback on it. Here are the the final report and the final presentation for this work.