Phonemic distance in dialects of Arabic

I worked on a phonemically-based way to compute the distance between two dialects of Arabic. This was work for my second qualifying paper for the PhD program at the University of Chicago.

Overview

This was the work done for my second qualifying paper for the PhD program in linguistics at the University of Chicago; the readers were John Goldsmith and Jason Riggle. This was really the first time I waded out into the deep end of independent research with really no one but myself to direct what I was doing; luckily, John and Jason afforded me the precious opportunity to do this and grow (not all graduate students are as fortunate to do this). The idea behind this work was to try to get a sense of the distance between two dialects of Arabic. Arabic is interesting because it has many dialects, but all of them are close enough to be comparable; moreover, Arabic has an established standard dialect as well, known as Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). It’s the coupling of these two facts which facilitates the comparison of dialects: in other words, comparing dialects becomes much easier when you have a reference point you can fix for those comparisons! In a way, you can think about it in terms of Pythagorean’s Theorem: if you know the distance of one dialect from the standard variety and you know the distance of another dialect from the standard, then you also can compute the distance between the dialects.

Inspiration / launching point for this work

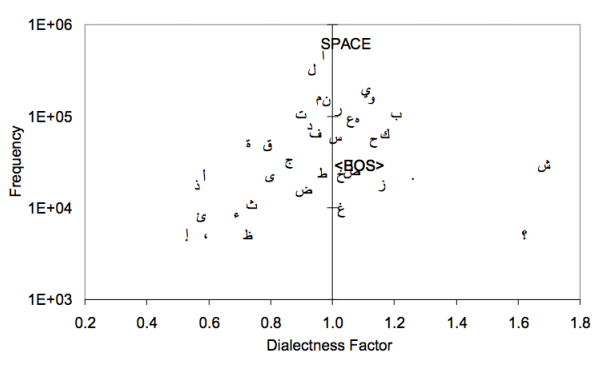

I became inspired to do this project for a couple of reasons: (i) I love the Arabic language; and (ii) there was an amazing paper by Zaidan and Callison-Burch pertaining to Arabic dialect identification. In the paper, the authors were concerned with the classification task of identifying dialects of Arabic, where they focused on the whole-word, or morpheme level (by morpheme, you can think in plain English as words). Although they included the plot you see below in their paper, they did not pursue dialect identification at the phonemic level (by phoneme, you can think in plain English as speech sounds). I wanted to extend their work by looking at differences between dialects at a phonemic level, and then I eventually ended up taking the project in a less practically-oriented direction. My goal became not to perform a classification task well but to better understand the differences between the dialects.

Dialectness factor

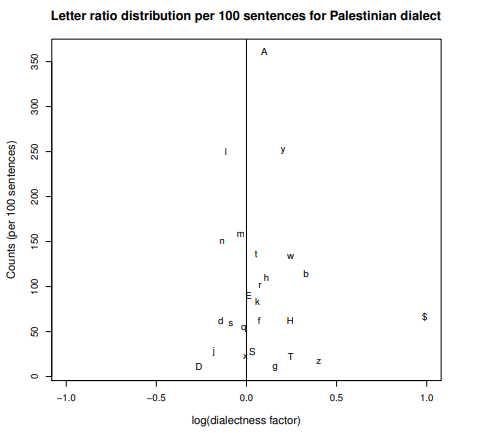

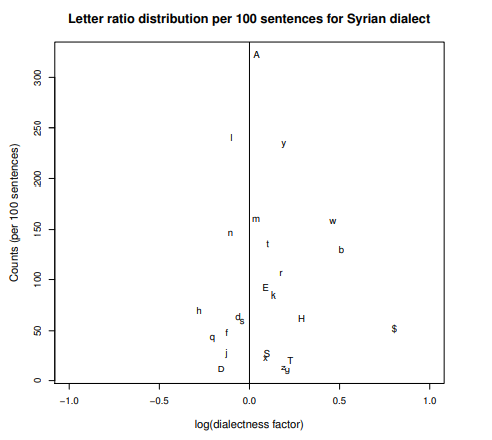

I was fortunate enough to get my hands on the PADIC corpus (A Parallel Arabic DIalect Corpus); this was amazing because it was translated phonemically in parallel.1 This corpus contained translations for two dialects in Algeria, the Algiers and Annaba dialect, and then the general dialects of Morocco, Palestine and Syria as well as Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). To get a sense for what phonemes were ‘dialectal’ and which were not, I compared how frequently one phoneme occured in a dialect versus how much it occurred in the standard, MSA. I did this by taking ratios, but I won’t go into the details here — please see the paper itself for those details. So, I was able to reproduce that plot you see above from Zaidan and Callison-Burch for each one of the dialects. I’ll just show the ones for the Palestinian (left) and Syrian (right) dialects.

Visualizing and comparing the dialectness factor

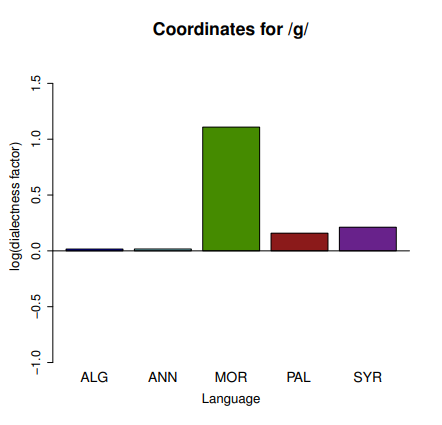

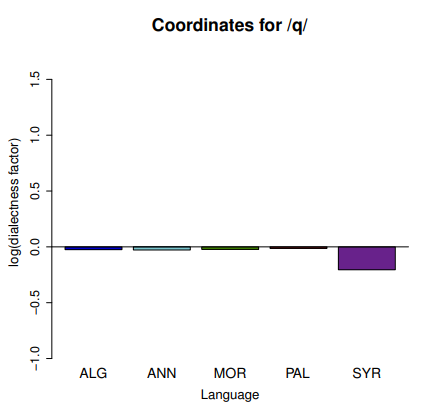

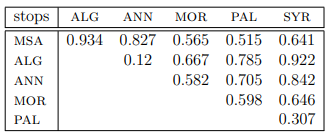

Once you compute the dialectness factor for each phoneme in each dialect, you can start to make comparisons, along many directions. First, you can look at comparisons for a single phoneme between different dialects, as you seen below. Any bar that extends above zero means the phoneme occurs more in a dialect, and if a bar extends below zero, it means that phoneme occurs less in the dialect (when compared to the standard, MSA). There are many more plots, but I’ll just provide a couple of plots, one for the sounds غ (left) and ق (right), which are similar to the French [r] sound and a hard [k] sound.2 These plots give us an idea of how each dialect is behaving.

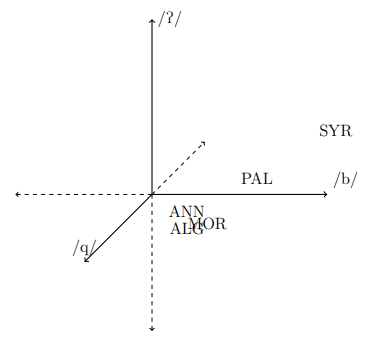

You can also look at the dialectness factors of classes of sounds which are similar to each other and then compare the dialects based on these class distances. Or, you can visualize where each of these dialects fall in some mathematical space, where each dimension corresponds to a phoneme! You can see these below. There is much more in my paper.

Upshot

At the end of this work, I basically developed a notion of phonemic distance, which was pretty interesting. This can be extended to more general situations, but it is tricky because my work depended on there being a standard, a point which we fix so that we can make comparisons. There is not really a clear point like this when you are doing comparisons between different languages. However, this project changed pretty profoundly my philosophy on what actually is a dialect and what actually is a language. The body of linguistic information for a given language or dialect can be mapped to a point in some high-dimensional linguistic space, and what we usually refer to as a ‘language’ is really just a limiting point in this space (borrowing language from topology, if I may), determined by cultural-historical forces, and dialects are just points within the a certain sized neighborhood of this limiting point.

Closing thoughts and more information

This is probably the most interesting work I think I’ve done, though, it was earlier in my development, so if I were to work on it again, I would approach it in a much more sophisticated way. :) Please do take a look at my actual paper if you are interested.